In content strategy, there is no playbook of generic strategies you can pick from to assemble a plan for your client or project. Instead, our discipline rests on a series of core principles about what makes content effective—what makes it work, what makes it good. The first section of this book is organized around these fundamentals.

There’s really only one central principle of good content: it should be appropriate for your business, for your users, and for its context. Appropriate in its method of delivery, in its style and structure, and above all in its substance. Content strategy is the practice of determining what each of those things means for your project—and how to get there from where you are now.

Let us meditate for a moment on James Bond. Clever and tough as he is, he’d be mincemeat a hundred times over if not for the hyper-competent support team that stands behind him. When he needs to chase a villain, the team summons an Aston Martin DB5. When he’s poisoned by a beautiful woman with dubious connections, the team offers the antidote in a spring-loaded, space-age infusion device. When he emerges from a swamp overrun with trained alligators, it offers a shower, a shave, and a perfectly tailored suit. It does not talk down to him or waste his time. It anticipates his needs, but does not offer him everything he might ever need, all the time.

Content is appropriate for users when it helps them accomplish their goals.

Content is perfectly appropriate for users when it makes them feel like geniuses on critically important missions, offering them precisely what they need, exactly when they need it, and in just the right form. All of this requires that you get pretty deeply into your users’ heads, if not their tailoring specifications.

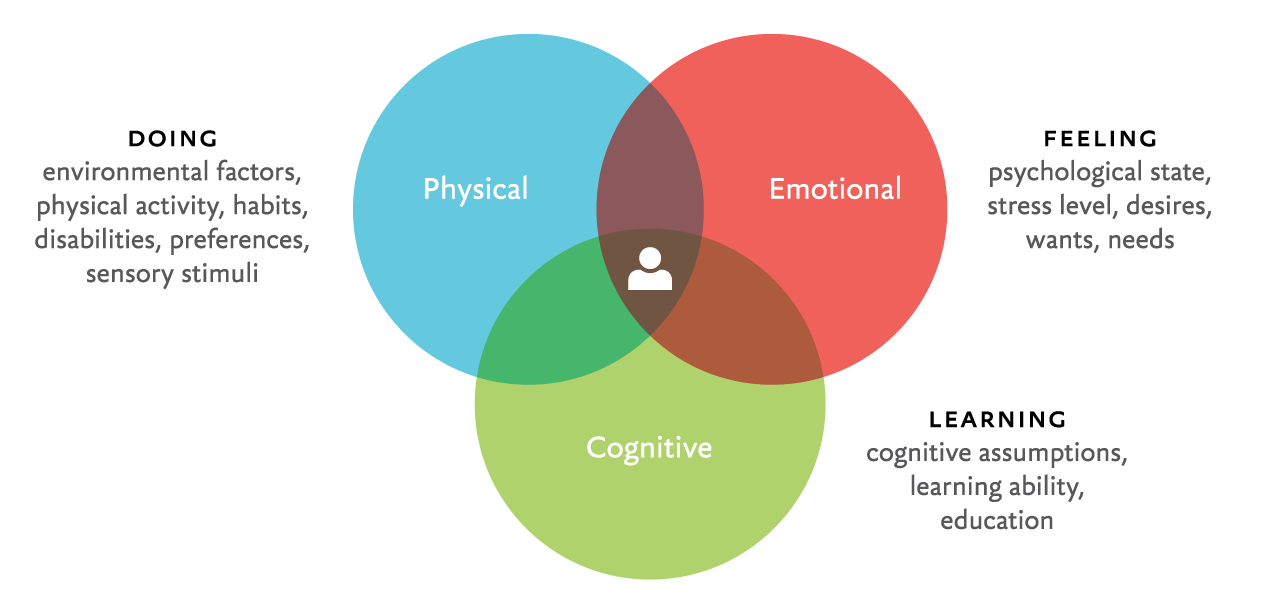

Part of this mind-reading act involves context, which encompasses quite a lot more than just access methods, or even a fine-grained understanding of user goals. Content strategist Daniel Eizans has suggested that a meaningful analysis of a user’s context requires not only an understanding of users’ goals, but also of their behaviors: What are they doing? How are they feeling? What are they capable of (fig 1)?

It’s a sensible notion. When I call the emergency room on a weekend, my context is likely to be quite different than when I call my allergy specialist during business hours. If I look at a subway map at 3:00am, chances are that I need to know which trains are running now, not during rush hour tomorrow. When I look up your company on my phone, I’m more likely to need basic contact info than your annual report from 2006. But assumptions about reader context—however well researched—will never be perfect. Always give readers the option of seeing more information if they wish to do so.

Fig 1: The user’s context includes actions, constraints, emotions, cognitive conditions, and more. And that in turn affects the ways in which the user interacts with content. (“Personal-Behavioral Context: The New User Persona.” © Daniel Eizans, 2010. Modified from a diagram by Andrew Hinton.)

Content is appropriate for your business when it helps you accomplish your business goals in a sustainable way.

Business goals include things like “increase sales,” “improve technical support service,” and “reduce printing costs for educational materials,” and the trick is to accomplish those goals using sustainable processes. Sustainable content is content you can create—and maintain—without going broke, without lowering quality in ways that make the content suck, and without working employees into nervous breakdowns. The need for this kind of sustainability may sound boneheadedly obvious, but it’s very easy to create an ambitious plan for publishing oodles of content without considering the long-term effort required to manage it.

Fundamentally, though, “right for the business” and “right for the user” are the same thing. Without readers, viewers, and listeners, all content is meaningless, and content created without consideration for users’ needs harms publishers because ignored users leave.

This principle boils down to enlightened self interest: that which hurts your users hurts you.

Few people set out to produce content that bores, confuses, and irritates users, yet the web is filled with fluffy, purposeless, and annoying content. This sort of content isn’t neutral, either: it actively wastes time and money and works against user and business goals.

To know whether or not you have the right content for a page (or module or section), you have to know what that content is supposed to accomplish. Greater specificity produces better results. Consider the following possible purposes for a chunk of product-related content:

Now do the same for every chunk of content in your project, and you’ll have a useful checklist of what you’re really trying to achieve. If that sounds daunting, think how much harder it would be to try to evaluate, create, or revise the content without a purpose in mind.

On a web project, user-centered design means that the final product must meet real user needs and fulfill real human desires. In practical terms, it also means that the days of designing a site map to mirror an org chart are over.

In The Psychology of Everyday Things, cognitive scientist Donald Norman wrote about the central importance of understanding the user’s mental model before designing products. In the user-centered design system he advocates, design should “make sure that (1) the user can figure out what to do, and (2) the user can tell what is going on” (Donald Norman, The Psychology of Everyday Things, p. 188).

When it comes to content, “user-centered” means that instead of insistently using the client’s internal mental models and vocabulary, content must adopt the cognitive frameworks of the user. That includes everything from your users’ model of the world to the ways in which they use specific terms and phrases. And that part has taken a little longer to sink in.

Allow me to offer a brief illustrative puppet show.

While hanging your collection of framed portraits of teacup poodles, you realize you need a tack hammer. So you pop down to the hardware store and ask the clerk where to find one. “Tools and Construction-Related Accessories,” she says. “Aisle five.”

“Welcome to the Tools and Construction-Related Accessories department, where you will find many tools for construction and construction-adjacent activities. How can we help you?”

“Hi. Where can I find a tack hammer?”

“Did you mean an Upholstery Hammer (Home Use)?”

“… yes?”

“Hammers with heads smaller than three inches are the responsibility of the Tools for Home Use Division at the far end of aisle nine.”

…

“Welcome to The Home Tool Center! We were established by the merger of the Tools for Home Use Division and the Department of Small Sharp Objects. Would you like to schedule a demonstration?”

“I just need an upholstery hammer. For … the home?”

“Do you require Premium Home Use Upholstery Hammer or Standard Deluxe Home Use Upholstery Hammer?”

“Look, there’s a tack hammer right behind your head. That’s all I need.”

“DIRECTORY ACCESS DENIED. Please return to the front of the store and try your search again!”

Publishing content that is self-absorbed in substance or style alienates readers. Most successful organizations have realized this, yet many sites are still built around internal org charts, clogged with mission statements designed for internal use, and beset by jargon and proprietary names for common ideas.

If you’re the only one offering a desirable product or service, you might not see the effects of narcissistic content right away, but someone will eventually come along and eat your lunch by offering the exact same thing in a user-centered way.

When we say that something is clear, we mean that it works; it communicates; the light gets through. Good content speaks to people in a language they understand and is organized in ways that make it easy to use.

Content strategists usually rely on others—writers, editors, and multimedia specialists—to produce and revise the content that users read, listen to, and watch. On some large projects, we may never meet most of the people involved in content production. But if we want to help them produce genuinely clear content, we can’t just make a plan, drop it onto the heads of the writers, and flee the building.

The chapters that follow will discuss ways of creating useful style guides, consulting on publishing workflow, running writing and editorial workshops, and developing tools like content templates, all of which are intended to help content creators produce clear, useful content in the long term.

Of course, clarity is also a virtue we should attend to in the production of our own work. Goals, meetings, deliverables, processes—all benefit from a love of clarity.

For most people, language is our primary interface with each other and with the external world. Consistency of language and presentation acts as a consistent interface, reducing the users’ cognitive load and making it easier for readers to understand what they read. Inconsistency, on the other hand, adds cognitive effort, hinders understanding, and distracts readers.

That’s what our style guides are for. Many of us who came to content strategy from journalistic or editorial fields have a very strong attachment to a particular style—I have a weakness for the Chicago Manual of Style—but skillful practitioners put internal consistency well ahead of personal preferences.

Some kinds of consistency aren’t always uniformly valuable, either: a site that serves doctors, patients, and insurance providers, for example, will probably use three different voice/tone guidelines for the three audiences, and another for content intended to be read by a general audience. That’s healthy, reader-centric consistency. On the other hand, a company that permitted each of its product teams to create widely different kinds of content is probably breaking the principles of consistency for self-serving, rather than reader-serving, reasons.

Some organizations love to publish lots of content. Perhaps because they believe that having an org chart, a mission statement, a vision declaration, and a corporate inspirational video on the About Us page will retroactively validate the hours and days of time spent producing that content. Perhaps because they believe Google will only bless their work if they churn out dozens of blog posts per week. In most cases, I think entropy deserves the blame: the web offers the space to publish everything, and it’s much easier to treat it like a hall closet with infinite stuffing-space than to impose constraints.

So what does it matter if we have too much content? For one thing, more content makes everything more difficult to find. For another, spreading finite resources ever more thinly results in a decline in quality. It also often indicates a deeper problem—publishing everything often means “publishing everything we can,” rather than “publishing everything we’ve learned that our users really need.”

There are many ways to discover which content is in fact needless; traffic analysis, user research, and editorial judgment should all play a role. You may also wish to begin with a hit list of common stowaways:

Once you’ve rooted out unnecessary content at the site-planning level, be prepared to ruthlessly eliminate (and teach others to eliminate) needless content at the section, page, and sentence level.

If newspapers are “dead tree media,” information published online is a live green plant. And as we figured out sometime around 10,000 BC, plants are more useful if we tend them and shape their futures to suit our goals. So, too, must content be tended and supported.

Factual content must be updated when new information appears and culled once it’s no longer useful; user-generated content must be nurtured and weeded; time-sensitive content like breaking news or event information must be planted on schedule and cut back once its blooming period ends. Perhaps most importantly, a content plan once begun must be carried through its intended growth cycle if it’s to bear fruit and make all the effort worthwhile.

This is all easy to talk about, but the reason most content is not properly maintained is that most content plans rely on getting the already overworked to produce, revise, and publish content without neglecting other responsibilities. This is not inevitable, but unless content and publishing tasks are recognized as time-consuming and complex and then included in job descriptions, performance reviews, and resource planning, it will continue.

Hoping that a content management system will replace this kind of human care and attention is about as effective as pointing a barn full of unmanned agricultural machinery at a field, going on vacation, and hoping it all works out. Tractors are more efficient than horse-drawn plows, but they still need humans to decide where and when and how to use them.

No matter how we come to content strategy, or what kind of content strategy work we do, these shared principles and assumptions underlie our work. Of course, these principles didn’t emerge from a vacuum. Content strategy is a young field, but it has evolved from professions that are anything but new. To understand the full scope of what content strategy can do—and to understand why it isn’t “just editing” or “another word for marketing,” let’s take a look at the professions that have laid the groundwork for our practice.